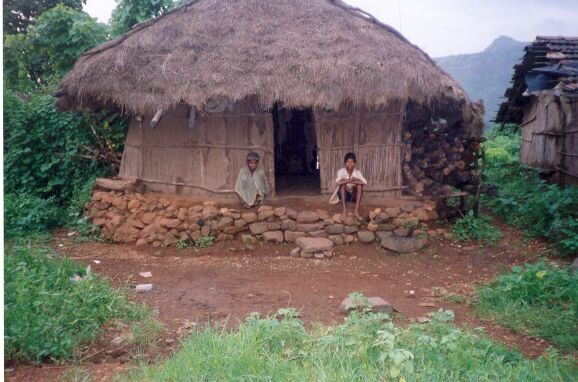

Tribal peoples like the Warli, Konkan, and Katkari are considered to be the oldest inhabitants of India. The villages of tribal people are made up of several hamlets or padas, with the houses in each pada constructed very close to each other with 10 to 15 members of a tribe, but at some distance from the fields.

Their main occupation is subsistence agriculture, although some of them also collect and sell forest produce. These indigenous communities have lived for centuries in the forest and hilly regions; today they still live in abject poverty.

These primitive farming and forest peoples barely eke out a living largely reliant on farming small plots of land for their nutritional needs. Over the last decades erratic rainfall has worsened the food situation and many tribal adults have been forced to migrate to nearby cities in search of employment; all too often children are left alone to care for younger kids and for themselves.

“Safety and health ought to be any child’s basic rights. But tribal children have little to no access to either” explains Father Alfons Schumacher, Franciscan Friar from Germany. Tribal women don’t receive pre-natal care, children lack proper nutrition and are often born with genetic disorders like sickle cell anemia and thalassemia, which are especially common among the Katkaris, Warlis and Konkanas.

Today India accounts for about 40% of undernourished children in the world, which contribute to high morbidity and mortality rates in the country. Recently, deaths among members of tribal communities went up prompting the commission of an investigation into the causes and factors.

The study collected information from 118 households in 4 villages in Maharashtra and examined through clinical analysis factors such as hygiene, dietary intake, and general socio-economic status. The results indicated that the health status of mothers, unhygienic environmental conditions, malnutrition, insanitary water supply, lack of protection against climate, and some harmful social customs and practices were some of the causes for the extensive prevalence of diseases and deaths among tribal populations.

Compounded with the absence of proper medical clinics and health care workers, tribal populations are among the most vulnerable and marginalized sections of society. “Lack of healthcare and the absence of adequate sources of income push many indigenous people into hopeless choices: either starve or migrate” says Father Alfons.

Tribal Children and Their Welfare

Many migrate to nearby cities and end up working in salt and sand extraction, brick kilns, fishing boats, construction, and railway and road constructions. Most tribal migrant workers are considered unskilled daily laborers, and they are all too often exploited physically, mentally and financially.

Tribal families typically have 4 or 5 children in each family, between the age group 1 and 7. Migration of the adults affects negatively the growth and development of the tribe.

But it is tribal children who are especially impacted because when the parents are away they stop attending school.

Elder kids look after the younger siblings while the adults are at work, and they are also involved in helping with livestock, fetching water, and cleaning. Therefore, tribal children are either not enrolled in the schools and among those who are there is high absenteeism.

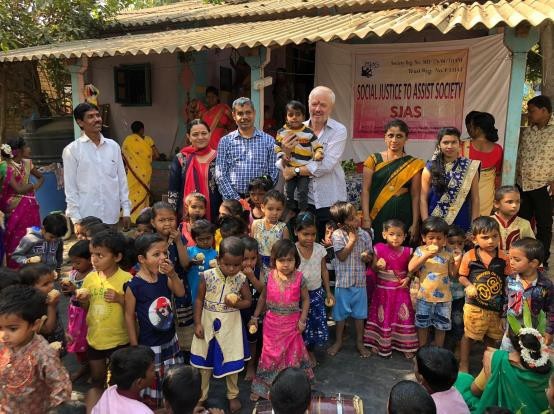

“Education can serve as a strategy to help the next generation of tribal families secure a better future” explains Father Alfons “nonprofit organizations like Social Justice to Assist Society (a ministry of the Franciscan Friars of Germany) is working across the Palghar district of Maharashtra to empower tribal and rural communities through early childhood education for children in the remotest hamlets of Vasai block of Palghar district”.

When adults are away at work, children are left alone with no one there to look after them. “Being able to attend two hours of kindergarten classes every day would achieve many important purposes for these tribal children” comments Anton Thomas, project manager for the Kindergarten 2021 Initiative.

He continues, “young children would be in a save place while their parents and elders are away from home, they would begin receiving a proper education, and they would also receive nutritional meals while attending their classes”. In 2021, Fr Alfons from SJAS turned to the Anthonian Association for financial assistance in order to provide free kindergarten for five classes of 25 to 30 kids in 5 villages of Vasai Taluka, serving a total of 125 tribal children.

Breaking the Cycle of Despair

The program would also employ, educate and trained youth from the villages who would conduct the classes. Local women would help as caretakers, and nutritious meals would be served to the children attending kindergarten classes. Teachers and caretakers would also receive ongoing training as to improve their educational skills and knowledge.

The kindergarten classes would meet Monday through Saturday. “The impact of such early childhood educational intervention would be felt by the entire family” remarks Fr Alfons“.

He continues, “we are involving parents through home visits convincing them of the importance of providing academic support to their children, while also providing a safe place and nutritional meals in their absence … moreover, children will be taught through early childhood teaching methods”.

Ensuring parents’ involvement, by asking them to sign up for responsibilities such as gathering the children for class and conducting inspections, ensures that children feel supported by the elders, spend time in a safe environment, and develop the habit of going to school. Moreover, with proper supervision, they can ensure that the food being eaten is safe for consumption. Poor hygiene when handling or eating food can lead to the harmful spread of germs, which can cause foodborne diseases and in severe cases even death.

Education and the End of Poverty

Education is one of the most important strategies tribal peoples have to combat poverty and lack of motivation to attend school, from both parents and children. Illiteracy among tribal adults and children is endemic; educational infrastructure is inadequate, teachers are irregular and often use archaic teaching techniques, and children drop out from school.

In Maharashtra, almost 89 per cent of schools in rural areas are functioning in multi-grade settings, where one or two teachers have to teach a large number of classes simultaneously. Mr. Anton Thomas, project manager of the Kindergarten Initiative explains, “because of so few teachers, tribal schools have adopted the system of self-learning and multi-grade classrooms, leaving tribal children at a serious disadvantaged as regards to their education.”

But the result of not fighting for children’s rights to early childhood education has lasting and devastating consequences for the entire community, comments Father Alfons, “for another generation is caught up in the cycle of illiteracy and poverty. his vicious cycle of struggle for survival makes it impossible for them to live a decent life.”

In this agony to make a day-to-day living, opportunities for education naturally take a back seat for most tribal families. Providing marginalized tribal children with an education head start and also regular nutritious meals is sure to lead to better health outcomes. With supervision and encouragement children, their parents, teachers and caregivers, can begin a new cycle of hope, which will likely lead to more positive habits later in life.

Thanks to the support of St Anthony’s followers and devotees, a grants in the amount of $13,000 was awarded to Social Justice to Assist Society (SJAS) to subsidize the costs of providing quality early childhood education to 125 economically disadvantaged tribal children of Vasai Taluka, India.